A Data Engineering Lesson for AI Agent Builders

Nobody can agree on what an agent is, but most definitions share a common thread: it’s software that uses an LLM to take actions, not just generate text. It can read files, call APIs, run commands, and make decisions based on what it finds. I wrote more about this in my post on tool calling and file system access.

Foundation Capital’s article on context graphs has been circulating widely, and NLW covered it on his podcast. The core idea: as agents orchestrate decisions across companies, they can capture the reasoning and context that led to specific outcomes. This information currently lives in Slack threads, people’s heads, or nowhere. Agents are in the execution path. They can record it.

One piece of their argument that I think deserves more attention: don’t over-constrain the format of what you capture. Let the agent figure out what belongs in the trace. This connected to something I learned years ago in data engineering.

The Web Scraping Lesson

At CircleUp, we were building an authoritative data set for understanding consumer packaged goods - what products existed, what brands were out there, where they were sold, how they changed over time. A core part of this was pulling in unstructured data from various sources. One example: scrapers that collected product information from brand websites and retailers - prices, descriptions, SKU numbers, ingredients. We cared about this data over time, not just a snapshot. We wanted to track how products changed month to month.

The MVP version of these scrapers transformed data inline. We’d find the HTML elements for the attributes we wanted, extract those values, and store them in a database.

Then someone asked about ingredient changes. We could add ingredient tracking going forward, but what about the historical data? Products that had reformulated - we couldn’t see what their ingredients used to be. We’d thrown away everything except the fields we thought we needed.

We caught this early and fixed it. The fix: store the entire HTML page, even if you only need three fields right now. Storage is cheap. You can’t recreate the ability to extract new information from historical data. The lesson stuck.

Once you learn this, your brain gets tuned to ask: what should I be storing that I’m not? API responses where you only need one field? Store the full payload. Event streams you’re filtering? Keep the raw stream somewhere. You can always add structure later. You can’t go back and capture what you didn’t store.

Decision Traces Are the Same Problem

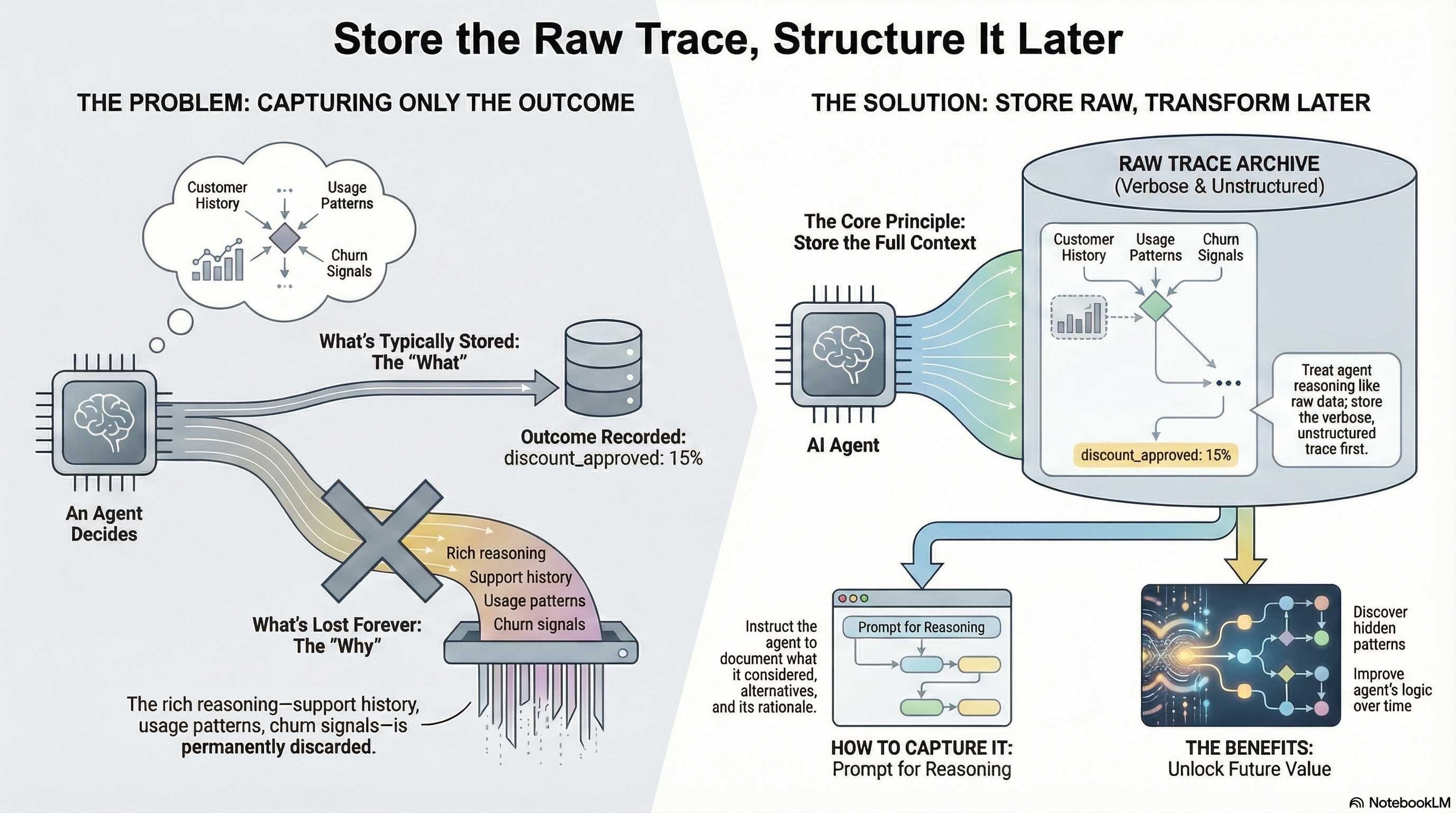

Agent reasoning works the same way. Consider an agent handling subscription renewals. A customer asks for a discount. The agent checks their support ticket history - three escalations in the past quarter, two unresolved for over a week. It looks at usage patterns - engagement dropped 40% after the last outage. It reviews similar customers who churned and spots warning signs. Based on all this, it recommends a 15% discount to retain the account.

Most systems would only capture the outcome - a field in the CRM that says “discount: 15%”. The reasoning - the support history it reviewed, the usage patterns it analyzed, the churn signals it identified, the similar cases it compared against - gets thrown away.

Systems of record capture state. They don’t capture decision lineage. The Foundation Capital article calls the accumulated decision lineage a “context graph” - traces stitched together over time so precedent becomes searchable.

The connection to my document generation agents post is direct. I called it “context tracing” - asking the model to generate a decision log alongside its output. What was considered? What was rejected? Why did it rate this evidence as strong vs. weak?

But I prescribed a specific format for those traces because I was targeting specific document types. Reading about context graphs made me reconsider: should I loosen those constraints?

Why Unstructured Traces Are Better

The natural approach is to define a schema for decision traces upfront. But if you lock in a structure too early, you limit what you can extract later.

Models are good at turning unstructured data into structured data - assuming the information exists in the unstructured source. If it’s not there, no post-processing will create it.

Verbose, unstructured traces let you change your mind. You can extract different structures later for different purposes. You can ask the model to create different views on the same data.

You can also discover patterns you didn’t anticipate. If you’re capturing verbose reasoning and later notice your agents consistently make similar exceptions for a certain type of customer, that’s a pattern you can codify - or at least understand. Structured traces with predefined fields would never surface it.

This is the data engineering pattern: store raw, transform on read. Store the full HTML. Later run Spark or DuckDB to extract whatever structure you need. If your transformation logic has bugs, fix it and rerun. The raw data is your source of truth.

With decision traces, the transformation uses an LLM instead of traditional ETL. More expensive per run, but negligible compared to not having the data at all.

Context Engineering for Tracing

Unstructured doesn’t mean effortless. You still have to invest in the prompts and context that tell the agent how to trace its reasoning.

You can’t just say “capture a decision trace.” You have to define what that means - but in terms that don’t constrain what the model can include. The instructions should describe what kinds of reasoning to document, not a rigid schema.

Something like: “For each decision, document what information you considered, what alternatives you evaluated, what made you choose this option over others, and any uncertainty you have about your choice.” Specific enough to be useful. Doesn’t prescribe fields or formats.

The decision trace is almost as important as the decision itself. Once you’ve collected enough traces, you can use an LLM to distill learnings from them. Ask it what patterns it notices. Take a contrarian approach: “What should we be doing differently based on these traces?” Having that information gives you more to work with as you iterate. The traces feed back into improving the agent.

The One-Way Door

Some decisions are hard or impossible to reverse. Choosing not to capture decision traces is one of them. Each agent execution generates reasoning that, if not recorded, is sealed away.

Most people building agent systems focus on getting to the right decision. What’s the correct discount rate? Did the agent extract the right claims? That matters. But if you’re only optimizing for the immediate output, you’re walking through one-way doors with every execution.

The clearest path to keep this door two-way: capture unconstrained, verbose decision traces. Give real thought to how you instruct the agent to do this. It’s a core part of your system design.

Store the raw trace. Structure it later.