Four Building Blocks for Document Generation Agents

A document generation agent takes information scattered across many sources and produces a coherent output that aligns with a specific structure. The input information is often duplicated, stated in ways that aren’t clear, and almost always unstructured. The agent’s job is to aggregate and transform all of that into something useful - which is generally something like a report, a summary, or a structured dataset.

This is one flavor of AI agent I’ve been building. There are others, but document generation is where I’ve been spending the most time recently. I wanted to write a bit about how I think about building these.

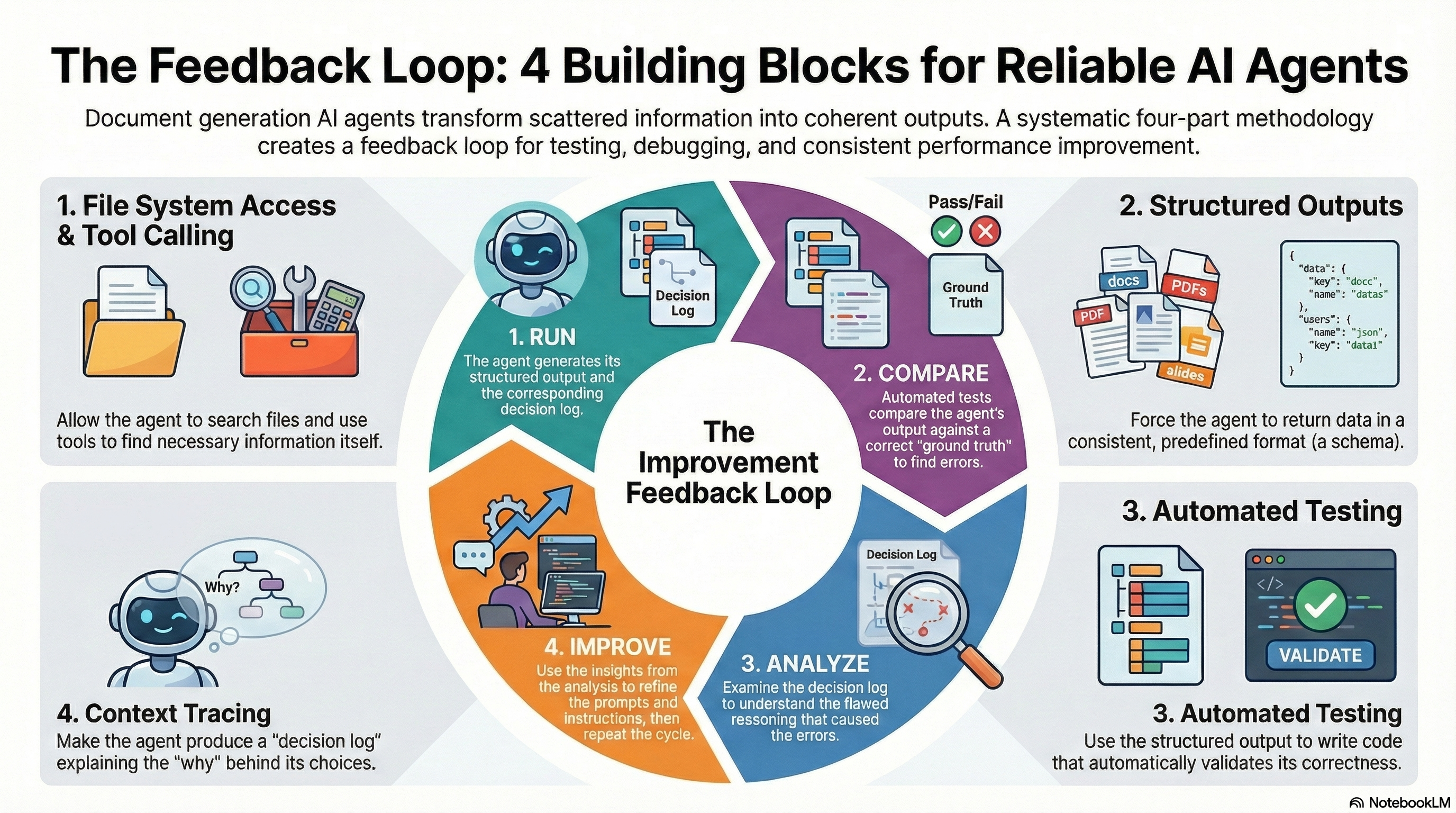

There are many ingredients that matter, but four have been most important in my experience: file system access and tool calling, structured outputs, automated testing, and context tracing. Each matters on its own. Combined, they form a feedback loop where you can systematically make your agent’s outputs better.

File System Access and Tool Calling

Models are good at finding what they need when they have access to tools. Raw file access and basic command line utilities - grep, ls, file reading - get agents surprisingly far. The model can search through the files, find relevant context, and pull in what it needs without you having to pre-specify everything in your prompts up front.

Claude Code and similar agentic tools work this way. You give the model access to search and read files, and it figures out what to look at. This matters for document generation because your source material is often spread across many files, and the model performs better by navigating that on its own.

You can also build custom tools for specific tasks - for example, a tool that queries a database, or one that fetches data from an API. But if you have access to raw text, the built-in file system tools handle most of what you need. You might need to pre-stage data by calling APIs or converting documents to text first, but once it’s accessible as files, the model can take it from there. Give the model the ability to explore and retrieve context dynamically rather than requiring you to manually assemble everything and stuff it into the context window.

Structured Outputs

One core challenge in document generation is turning unstructured input into a consistent format. Most input data is raw text - not nicely defined tables or structured formats. But reports typically have a formulaic structure. There’s a mismatch between what you have and what you need to produce.

Instead of expecting the model to handle the complexity of your unstructured instructions about what to extract, you give it the structure you demand. For research report generation, that might mean a list of claims, where each claim has a citation source, an evidence quality rating, and a source type classification. The model aligns its output to match your schema. Structured outputs are beneficial for a few reasons:

First, you can give field-specific instructions that constrain the model’s behavior. In the research report example, you might specify that each claim must include the exact page number from the source document, and that claims should only be included if they’re directly stated rather than inferred. The model follows field-level constraints more reliably than vague instructions about the overall output that are embedded within a system or user prompt.

In Python, libraries like Pydantic let you define structured output schemas directly in code:

class Claim(BaseModel):

statement: str = Field(description="The claim, directly stated from the source")

source_document: str

page_number: int = Field(description="Exact page where claim appears")

evidence_quality: Literal["strong", "moderate", "weak"]

source_type: Literal["primary_research", "secondary", "opinion"]

The field descriptions can become part of the instructions to the model. When the model generates output, it aligns to this schema.

Second, structured output as an intermediate step changes how you build the final document. Once you have validated structured data, you can use a templating system to generate the prose rather than having the LLM generate the final document directly. You’re breaking the problem into discrete steps: extract structured data, validate it, then render the final output from that validated structure. Each step is simpler and more testable than trying to do everything in one pass.

Structured Outputs Enable Testing

Looking at a wall of text and asking “is this correct?” is hard. You have to read the whole thing, mentally check each claim, verify that sources are present. It’s slow and you miss things.

Structured output makes validation more objective and concrete. You can write assertions in code. How many claims exist? Does a specific claim exist? Does each claim have a page number? Are there at least three sources from primary research? Is every citation formatted correctly? These become automated tests you can run every time you change your prompts.

Once you have tests, you can iterate. You can change your prompt, run the tests, and see what broke. This also allows you to do things like try a different model and compare the results. The tests give you freedom to experiment because you’ll catch regressions immediately.

There’s also a deeper point: Working with structured outputs forces you to articulate what correctness actually means and what the report actually needs to contain. You can’t write a test for “is this summary good?” But you can write tests for specific properties (as described above). This is different from throwing a long prompt at a model and getting a big text response. You’re breaking the problem into pieces where you can define and verify correctness for each one.

The schema also becomes common ground for working with subject matter experts. Instead of vague discussions about what the report should include, you can point to specific fields and ask: is this the right structure? What’s missing? What should the valid values be? It makes alignment concrete.

Testing can help you determine what’s wrong - but to fix it efficiently, you also need to know where the model went wrong.

Context Tracing

This is the piece that I think makes the biggest difference for improving your agent over time.

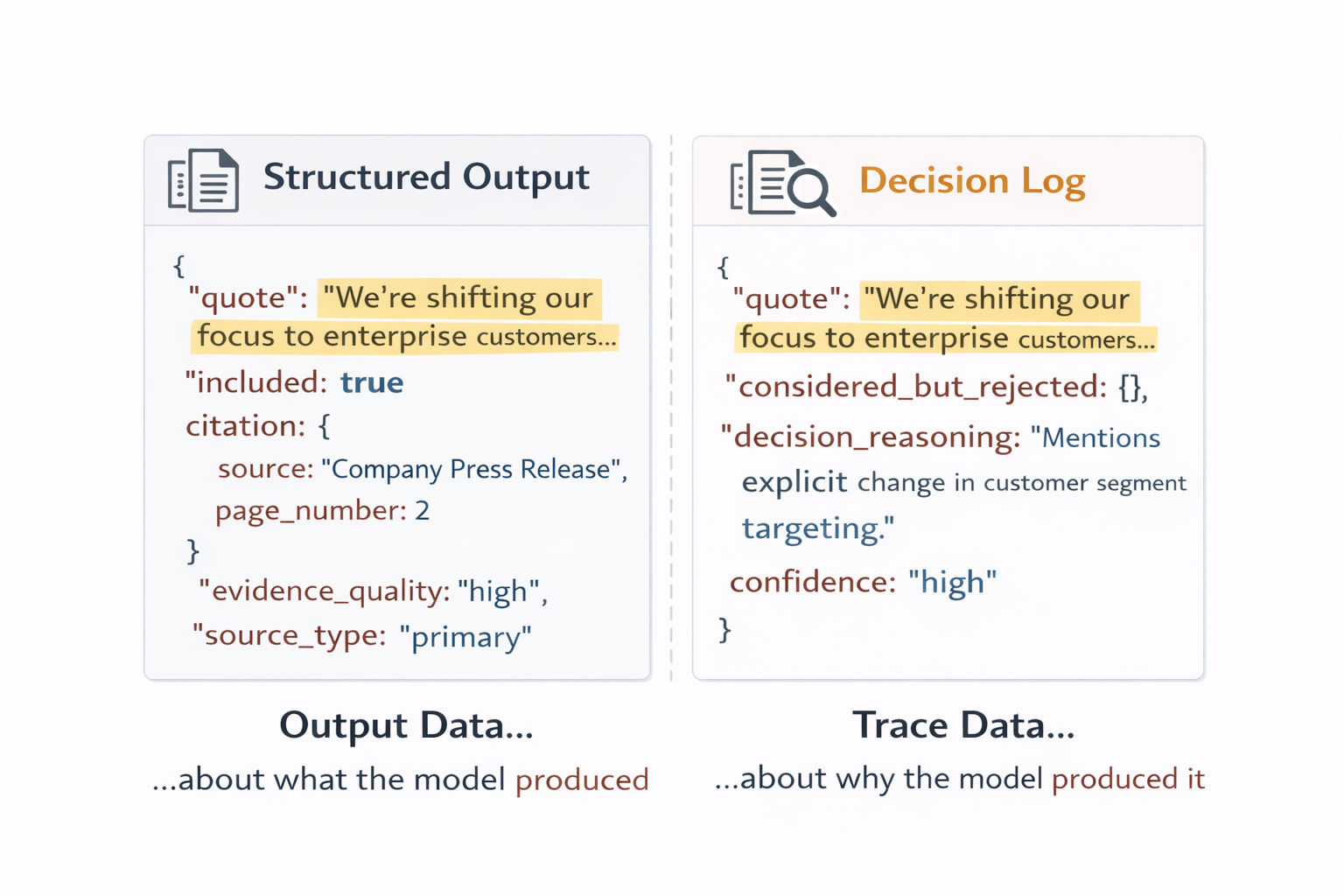

Structured output tells you what the model decided. It doesn’t tell you why. In the research report example, your structured output returns a list of claims with their citations. But it doesn’t show you which potential claims the model considered and rejected. It doesn’t explain why it rated one piece of evidence as strong and another as weak.

The structured output tells you what the model extracted. The decision log tells you why.

The structured output tells you what the model extracted. The decision log tells you why.

Context tracing is a term I use to describe asking the model to generate a decision log alongside its actual output. You ask the model to generate two things: the structured output you want, plus a separate structured output that describes how it made its decisions.

What goes in the decision log depends on your use case. Here are some examples of what you could include:

- For each extracted item, a brief explanation of why it was included

- Items the model considered but rejected, with the reason for rejection

- Reasoning behind subjective judgments (why “strong” evidence vs “moderate”?)

- Confidence levels for each decision

- Places where the instructions were ambiguous or the model was uncertain

For the research report example, a decision log entry might look like:

{

"claim": "The treatment showed 23% improvement over baseline",

"source_text": "Results demonstrated a 23% improvement over baseline (p<0.05, n=847).",

"included": true,

"inclusion_reasoning": "Quantitative finding with statistical significance, directly stated in results section.",

"evidence_quality_reasoning": "Rated 'strong' - controlled study with large sample size (n=847) and p-value reported.",

"confidence": "high"

},

{

"claim": "Side effects were minimal",

"source_text": "Adverse events were reported in 12% of participants, compared to 8% in the control group.",

"included": false,

"exclusion_reasoning": "The source text doesn't support 'minimal' - 12% vs 8% is a 50% increase in adverse events. This would be editorializing.",

"confidence": "high"

},

{

"claim": "This suggests the treatment could be effective for other conditions",

"source_text": "These results suggest the treatment mechanism could potentially benefit patients with related inflammatory conditions.",

"included": false,

"exclusion_reasoning": "Author speculation in discussion section. Per instructions: 'claims should only be included if directly stated rather than inferred.'",

"confidence": "high"

}

There’s an art to designing what to capture. You want enough information to debug problems and improve your prompts, but not so much that the reasoning overhead dominates the actual work.

The relationship to structured outputs is direct: both your actual output and your decision log are structured. You define schemas for both. The decision log is metadata about how the model produced the primary output.

The Feedback Loop

The whole point of these building blocks is that they combine into a feedback loop. The goal is that you can systematically improve your agent through automated testing and by giving domain experts the context they need to tell you exactly what’s wrong when the agent isn’t producing the correct results.

A key thing you do need to make this work is ground truth examples. For a set of use-cases, what is the correct answer? What would the agent return if it were 100% correct? This takes time to build and is often tedious work, but you need something to compare against.

Once you build a few of these ground truth outputs, you can run your agent and compare its output to your ground truth. I use pytest to orchestrate these tests. Because you’re using structured outputs, you can programmatically identify exactly which fields are wrong - not just that “something seems off,” but specifically which claims are missing, which citations are wrong, which extractions are incorrect.

Once you have failing tests, the decision log, and the expected output, you can work to improve your prompts. Here’s the process I follow:

- Look at the specific fields that failed in your tests

- Find those fields in the decision log and read the model’s reasoning

- Identify the mismatch - did the model misunderstand the instructions, lack context, or make a judgment call you disagree with?

- Show the model the mismatch: here’s what you produced, here’s what I expected, here’s your decision log. Ask it to identify which instructions were unclear

- Share the outputs and the decision log with domain experts - they can often help you identify where the agent is making incorrect judgements.

- Update your context / prompts based on what you learn

- Run the agent and run the tests again

This is what people usually call ‘hill climbing’. The decision log is a great addition to this process because it captures reasoning you’d otherwise lose. Without it, you’re just looking at wrong outputs and trying to figure out why. With it, you have the model’s own explanation of its choices.

Tying It Together

The bigger point is that these systems are steerable. They’re stochastic and non-deterministic, but that doesn’t mean you’re at the mercy of randomness. If you build in the feedback loop, you can get high quality outputs and actually be positioned to improve them over time.

This is one feedback loop pattern among many. If you’ve spent time in machine learning or data science, you know how fundamental these loops are. What I’ve described here is what’s working for me right now with document generation agents. But the industry hasn’t settled on standard patterns yet. What works is still fluid.

That’s part of what makes this interesting. You get to experiment with what works for you. I’m curious how others are thinking about these problems - whether they’ve found different approaches to capturing model reasoning, different ways to structure the improvement loop, different building blocks entirely.

Either way, it’s a good time to be building these systems. The tools are capable enough to do real work, and the patterns for making them reliable are still being discovered.