How I Built a Portfolio Optimization Plan with Claude Code

I saw the below tweet recently and I did exactly this. Over multiple sessions with Claude Code, I fed it our brokerage CSVs, described our goals and constraints, and worked with it to produce a portfolio optimization plan - phased actions, tax impact analysis, fund recommendations, before-and-after allocation grids. The kind of plan you’d pay a financial advisor to put together, except I built it with an AI.

A year ago, I wrote about building a personal finance tool in a day with AI. That project required software development - I used AI to help me build an application with a UI, data pipelines, and visualization components. Models have gotten flexible enough that you don’t need to build an app anymore. An agent like Claude Code can read your files, write scripts, run them, and iterate on the output directly.

Setting Up the Workspace

I used Claude Code, which runs in a terminal and can read and write files on your machine. I pointed it at a directory with all my financial data. Portfolio analysis is a good fit for this because there’s a lot of messy data in different formats that the model can just dig through directly.

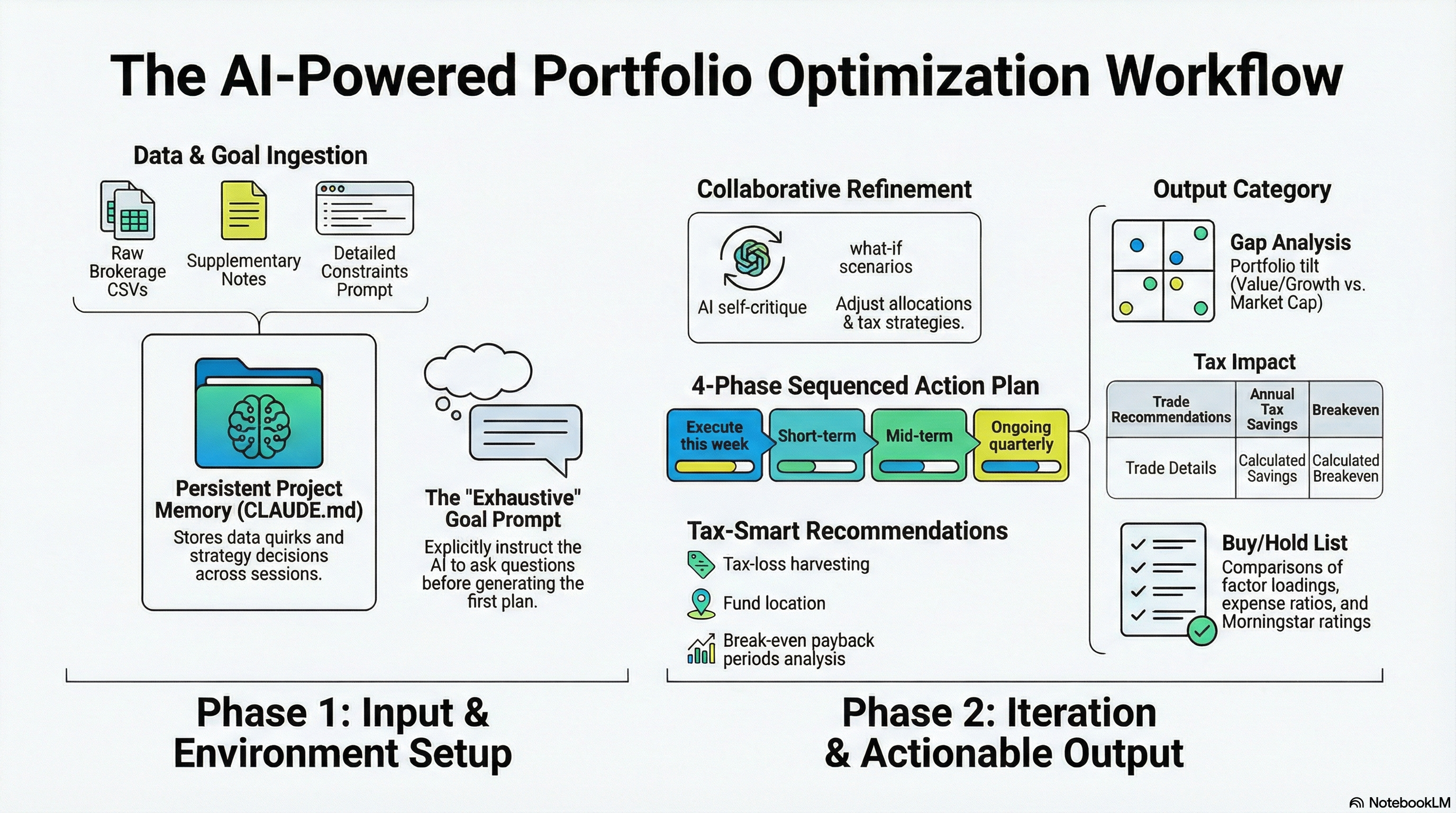

I started with three inputs:

- CSV exports from my various financial accounts - holdings, amounts, cost basis, fund fees, fund ratings, and a ton of other data the model could use

- A supplementary text file - there was other information I knew the model would need but no good way to export it, so I typed up a scratchpad with a bulleted list of things like bank balances, 529s, employer retirement account details, and automated investment settings. Not structured, but it had the raw numbers.

- A goal prompt describing what I wanted

The goal prompt was the most important piece. I spent a lot of time on it and wrote it mostly by hand before having the AI review it - I wanted to force myself to think through all of our constraints and goals. I included:

- What data exists and where - a narrative of what files are in the directory and what the model should be considering

- The desired output format - I brainstormed the kinds of things I wanted to see: allocation tables, style-box grids, holdings charts, different ways to slice the data. And ultimately, a concrete plan for how to modify the portfolio to get to a target allocation.

- Our preferences - I want the portfolio to be tax efficient, I’d rather find the lowest fee ETFs that are good than chase performance, and I don’t want to overcomplicate things. I’m well-versed in this stuff but complexity isn’t the goal.

- Known constraints - everyone has their own nuances. For us, we’d decided not to touch the allocations or ongoing contributions for a specific account, so I called that out as a constraint.

- What we suspected was wrong - I had a view on things that could be better, so I included it, but I caveated it with “if you have a different view, I want to hear it.” I didn’t want to oversteer the model toward a specific outcome. If you have insight that can nudge it in the right direction, it’s worth providing - just make sure you give it room to look outside your ideas too.

- Strawman proposals - I included our own rough ideas for target allocations and investment changes. Even if they’re wrong, it gives the model a starting point to react to rather than building from scratch.

- “Ask me questions exhaustively” - I put this at the end of the prompt. It gets the AI to ask clarifying questions before jumping straight to conclusions, which makes the first plan way better.

I also built up a CLAUDE.md file - project instructions that Claude reads at the start of every session. I had Claude set it up initially after asking me some questions, but after a couple sessions I started having Claude update it with any learnings from each session. Over time it became the project’s memory - data quirks, strategy decisions, target allocations. When I came back days later, Claude picked up right where we left off.

Parsing the Mess

Once I had the goal prompt and data ready, I handed the wheels over. Claude (Opus 4.6) worked for a while on its own - writing Python scripts to parse all the CSVs, classify every holding into target categories, handle encoding issues, deduplicate overlapping exports, and deal with non-standard line items that would get misclassified. It iterated through problems as it hit them and ended up in a really good place. The baseline it produced - a full gap analysis across every account and category - was impressive enough to start working from immediately.

Iterating as Thought Partners

The initial plan identified overweight categories, found tax-location violations, recommended specific fund swaps with expense ratio comparisons and Morningstar ratings, and calculated one-time tax costs versus ongoing savings. It even recommended tax-loss harvesting partner funds for every new position.

From there, it was like working with an analyst who has all the data but hasn’t lived with the accounts. I’d clarify something or reframe a constraint, and Claude would update every calculation, table, and recommendation in the plan. A few examples:

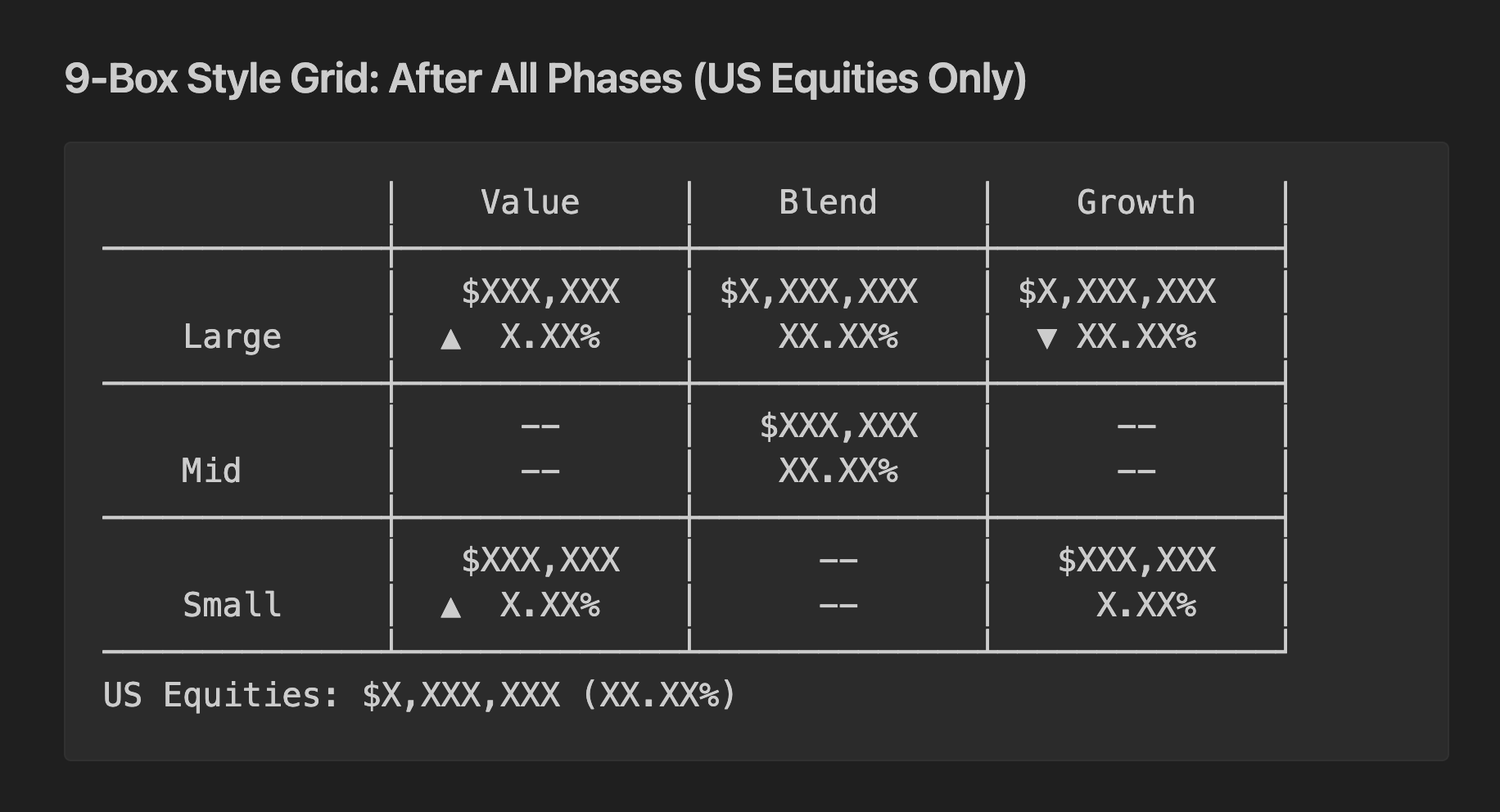

I refined our international allocation with Claude. The initial plan had a single “international” bucket, but I wanted more nuance - specific targets across value vs. growth, small vs. large. I worked back and forth with Claude to figure out what that breakdown should look like and which funds would get us there. That kind of allocation decision is hard to think through alone because every change affects the rest of the portfolio.

I asked Claude to self-critique - “rate this plan 1-10 and tell me what you’d change.” It gave itself a 7.5 and identified seven improvements. The biggest was hiding in plain sight: we had a large overweight position sitting in tax-free retirement accounts, where selling costs literally zero in taxes. The original plan had left it untouched. It also caught that its own retirement account deployment was putting money into a category that was already overweight. I approved the changes but asked for a phased approach rather than all-at-once.

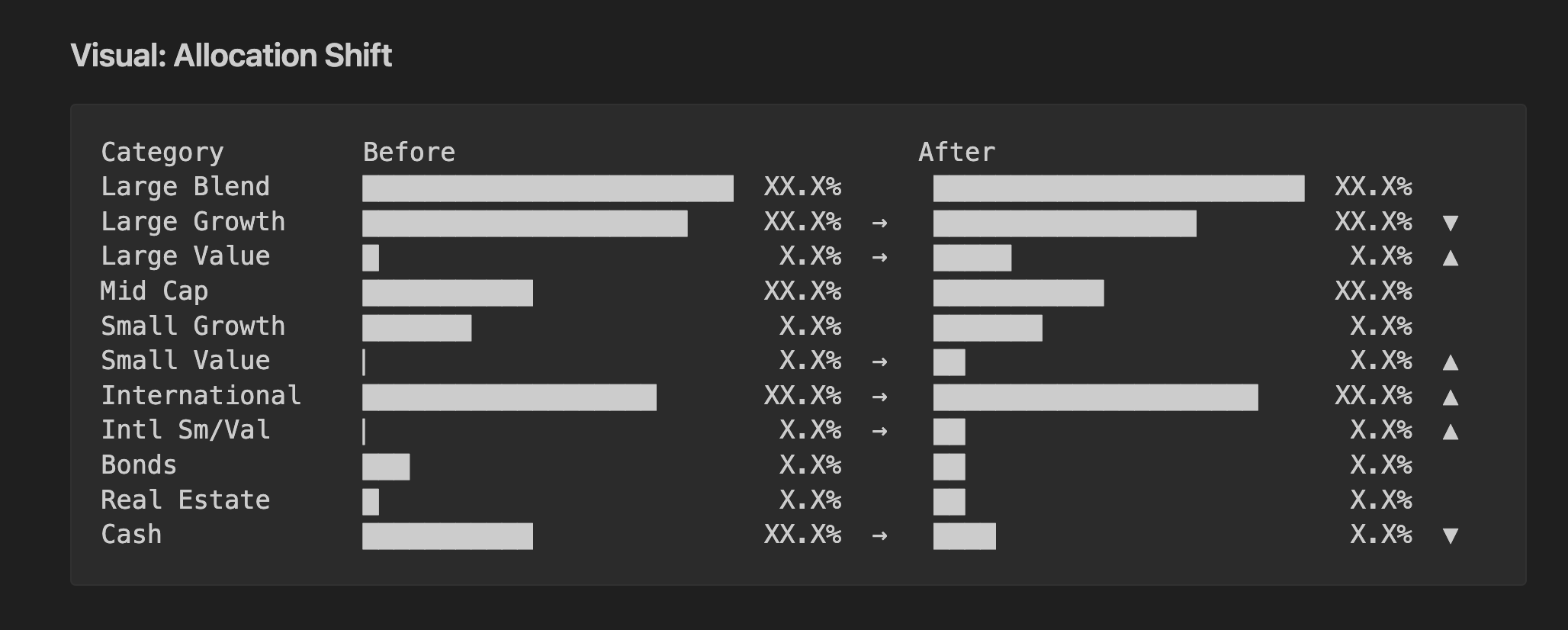

I reframed which accounts count toward targets. We decided to treat my wife’s employer retirement account as static for now - we wouldn’t touch it or change its allocations. This is an artificial constraint, but it simplifies the plan, and once we lock in the other changes we can always run the process again with new constraints if we want to modify that account later. The initial analysis left it out entirely. But it still holds real money in specific categories, and that affects what the rest of the portfolio needs to do.

Once I pointed this out, Claude built a combined framework quickly: define targets for the full portfolio, subtract what the static account provides, and optimize the rest to fill the gaps. Some overweight categories got worse, some underweight ones became more urgent, and the recommended purchases changed.

What It Produced

I ended up with a ten-section plan document with appendices - and several sections went beyond what I asked for:

- Complete portfolio snapshot - Every account, every holding, with cost basis, embedded gains, expense ratios, and tax treatment. All parsed automatically from the raw CSV exports.

- Gap analysis across ten fund categories - Current allocation versus targets, with the dollar gap and priority level for each. Included a visual bar chart showing the drift and a nine-box style grid (value/blend/growth vs large/mid/small) showing the portfolio tilt before and after.

- Combined portfolio framework - A table showing how an account we’d decided not to touch still changes the effective targets for the rest of the portfolio.

- Four-phase sequenced action plan - Concrete steps organized from “execute this week” through “ongoing quarterly.” Each action specified the fund, the dollar amount, the account, the tax cost, and the rationale. Separate actions for retirement accounts (zero tax) versus taxable (calculated tax impact).

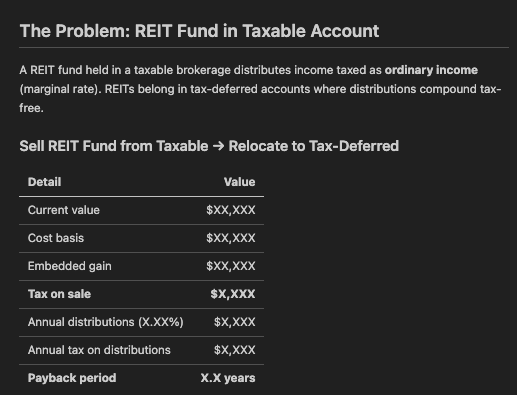

- Tax impact summary with payback periods - A table for every recommended trade showing the gain, tax cost, annual tax savings, and the breakeven timeline. A separate table for positions explicitly not recommended to sell - calculating the tax cost if you did sell and explaining why the math didn’t work.

- Fund recommendations with deep research - An active buy list, a stop-buying list, and a hold-and-dilute list. Claude compared candidates on factor loadings, expense ratios, Morningstar ratings, AUM, and whether they screen out low-quality companies. Each recommendation included a tax-loss harvesting partner: a similar-but-not-identical fund from a different provider, so if a position drops you can capture the loss and immediately buy the partner to maintain exposure without triggering wash sale rules.

- Tax location matrix - Which asset type belongs in which account type (pre-tax, Roth, taxable) and why, with a list of current violations and the action to fix each one.

- Retirement contribution structure optimization - Claude looked at my wife’s employer retirement contributions unprompted and found that switching one component from after-tax to pre-tax treatment would save thousands annually, with the ability to convert at much lower rates during early retirement.

- Natural dilution timeline - Projections for how long each overweight category takes to reach target through new money allocation alone, accounting for recurring contributions and dividend flows.

To be clear, this wasn’t a science experiment. I’m actively using this plan and I’m almost done executing it. I had Claude remix the full document into a shorter checklist so I can scan it and check things off as I go.

If You Want to Try This

- Export everything you can into files. Download CSV holdings from every brokerage account. Create a text file for anything without an export - bank account balances, employer retirement plan details (holdings, contribution amounts, fund options), automated investment settings, any pending changes you’re considering.

- Write a detailed goal prompt. State your tax situation, risk tolerance, and time horizon. List your constraints - accounts you don’t want to touch, positions you can’t sell, contribution limits. Include what you already suspect is wrong. Add a strawman target allocation if you have one - it gives the AI something concrete to react to. Ask for a sequenced action plan, not general advice. And end with “ask me questions exhaustively” - the AI will ask clarifying questions instead of filling in the blanks, so you’re not leaving anything ambiguous about what you actually want.

- Iterate like you would with a human advisor. The first plan will be solid but will miss things only you know about your accounts. Each clarification is fast; the AI updates every calculation in the plan instantly. Ask it to rate its own plan 1-10 - it’ll find things it missed.

- Build project context that persists. If you’re using Claude Code, a

CLAUDE.mdfile in your project directory carries across sessions. Add key decisions, data quirks, and what you’ve figured out as you go. Every future session builds on everything that came before.

The Work Compounds

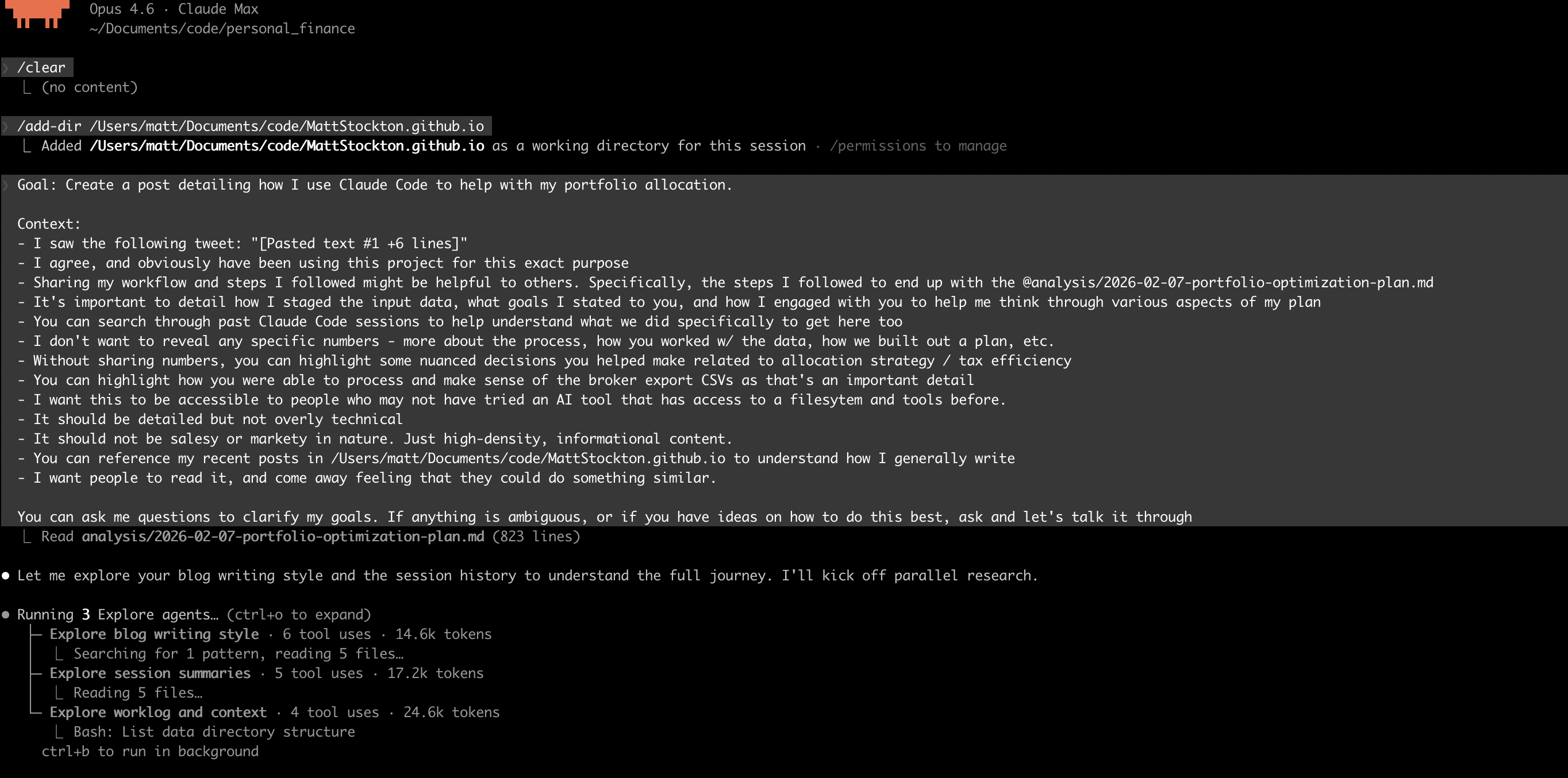

This blog post was written with the help of Claude Code. I pointed it at the same project directory, told it to read the session history and plan documents, and asked it to write a post about the process. The work you do with these tools compounds - you can distill it into other artifacts or remix it with other content. The prompt that kicked off this session:

Because the project context was already in the filesystem - the optimization plan, the session summaries, the strategy decisions - Claude had everything it needed to draft the post. I iterated on it from there, but the starting point was strong because all the context was already there from previous sessions.

A year ago this would have been a week of spreadsheet work or a few thousand dollars to a financial advisor. Instead it was a few evenings of back-and-forth with an AI, and the plan it produced is the one we’re executing.